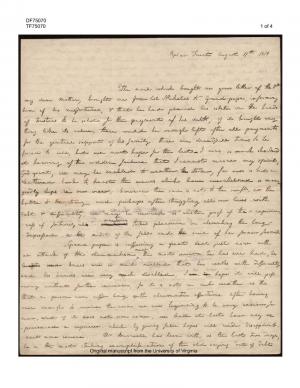

Ellen W. Randolph (Coolidge) to Martha Jefferson Randolph

| Poplar Forest August 11th 1819 |

The mail which brought me your letter of the 7th my dear Mother, brought one from Col. Nicholas to Grand-papa, informing him of his misfortunes, & that he had placed his estate in the hands of trustees to be sold for the payment of his debts; if it brought any thing like its value, there would be enough left after all payments for the genteel support of his family. these are dreadfull times to be forced to sell, but we must hope for the best—I was so much shocked at hearing of this sudden failure that I cannot recover my spirits; God grant, we may be enabled to weather the storm, for ours is but a shattered bark to breast the waves which have overwhelmed so many goodly ships in our view; however the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, and perhaps after struggling all our lives with debt & difficulty, we may be reserved as another proof of the capriciousness of fortune, which sometimes who sometimes takes pleasure in elevating the long-depressed amidst in the midst of the fall and the ruin of her former favorites.

Grand-papa is suffering a great deal just now with an attack of the rheumatism one of the most severe he has ever had; his hands and knees are so much swelled that he walks with difficulty and his hands are very much disabled; I am in hope it will pass away without farther increase, for it is not in such weather as this that a person can suffer long with rheumatic affections. After having rain enough to revive the corn we are beginning to be very anxious for more, and if it does not soon come, we shall at last have only experienced a reprieve, which by giving false hopes will render disappointment more severe.Mr Burwell has been with us the last two days, he is the most striking exemplification of the old saying “out of debt out of danger” that I have ever known. his manners preserve their serenity & his countenance its tranquility in the midst of the universal anxiety—curtail-day has no horrors for him; the thunders of the bank roll over his head, and leave him, as they found him, undismayed. if his corn crop fails he can has but to replace it with his wheat, and to live with his negroes & perhaps as they do, on the products of his farm, careless of foreign luxuries; and of the money which procures them, & which as he owes to no man he can very well do without, himself.

I think the prospect of soon having nothing to live on, makes people the more determined to live while they can—we have never been so much interrupted by visiting and invitations as since we have been here last; for the last three days the carriage has been ordered as regularly as the breakfast; yesterday we dined out with a large party, and have two invitations on hand for this week. our plans of industry are much disconcerted by all this—& I have never found my time pass so unpleasantly. the only compensation which could be offered me for the loss of my family society, was the uninterrupted indulgenc[e] of those pursuits most congenial to my taste, and the consciousness of time usefully, profitably, employed. my studies here were but rendering me more fit for the society to which I was to return, more capable of understanding all its value. [. . .] but now after the heat and toil of dressing, we leave home, at a time of day when the thermometer is perhaps at 95° in a little confined carriage which has got so thoroughly heated standing a few moments before the door, that it is like entering the mouth of an oven, & after a ride of four five or six miles thr over a rough dusty road under a broiling sun, we arrive fatigued, flushed and dirty, set up four or five hours in company, [. . .] silent and uncomfortable, too much exhausted to enjoy society if we had it even if it were of the best kind, and return home in the evening to mourn over the weary day and wasted hours. this sort of life seems however to agree with us both—I have never seen Cornelia look better or handsomer. [. . .]

Had it not been for these frequent interruptions, I should have done a great deal whilst I staid here—I am reading Virgil in latin & reading with as much difficulty as I do, I find that I shall never again tolerate a translation. Dryden whom I admired so much; there is as much difference between his Ænead & Virgil's as there is between a glass of rich, old, high flavored wine, and the same wine thrown into a quart of duck-water—even the passages which I admired the most I can now criticise without mercy. I have not advanced far in the original, & have discovered many beautifull passages, which I should never have suspected in the translati[on] & not only the general strength and spirit of the poem is lost, but the beauties of detail are pawed untill they lose all their bloom and freshness. I [. . .] feel disposed to quarrel with Dryden, [. . .] for his most trifling infidelities. in the description of the meeting of Venus & Eneas, in the woods;—“she turned and made appear, her neck refulgent & disheveled hair”, it should be, “ambrosial hair” which is the literal translation, as good measure, and I think a more elegant idea—the epithet, rosy, which is applied in the original “rosea cervice refulsit” is hardly included in our word refulgent. in another place I find the “fremet horridus ore cruento” of Virgil very badly rendered by “threats the world with vain alarms” which is not at all the same idea. you recollect it is in the description of [. . .] Fury, imprisoned during the happy reign of Augustus. If in stead of travelling about the country, from one hot-house to another, over roads perfectly answering the description given by Southey in his “cool reflections”, (to which literally way of spending time, “toasting cheese for Beelzabub, would be” literally “a cool employment”) I could only stay at home, and improve myself in a language, the knowledge of which promises to open to me so wide a field of enjoyment.

Adieu my dearest Mother, I never recollect that these d[. . .] may be tiresome to you, untill after they are written; [. . .]Give a great deal of love to every body, and accept for yourself the assurance of your daughter’s devotion.

Give my love to Papa particularly.

Mr Burwell desires me to open my letter to add his compliments &c.