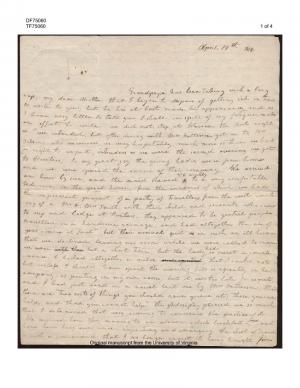

Ellen W. Randolph (Coolidge) to Martha Jefferson Randolph

| [Poplar Forest] April 14th 1818. |

Grandpapa has been taking such a long nap, my dear Mother that I began to despair of getting ink in time to write to you, but he has at last made his appearance, and as I have very little to tell you, I shall in spite of my fatigue, make an effort to write. we did not stop at Warren the first night as we intended, but after dining with Mrs Patterson got on to Mrs Gibson’s who received us very hospitably, much more so than we had a right to expect, intruders as we were. the second evening we got to Hunters; to my great joy the young ladies were from home and we were spared the ennui of their company. We arrived an hour by sun, and the maid shewed us V. & myself to a very comfortable bed room in the great house, from the windows of which we had the unpleasant prospect of a party of travellers from the west, consisting of a Mr &. Mrs Smith with their child and servants, who came to sup and lodge at Hunters—they appeared to be genteel people travelled in a handsome carriage, and had altogether the air of “gens comme il faut” but their arrival put us in such an ill humor that we declined leaving our room untill we were called to supper we were [. . .] with them but a short time, but the lady had so sweet a countenance, & looked altogether so mild and genteel, that I could not but confess, I should have spent the evening full as agreably in her company, as pouting in my own room; but it was too late for regrets, and I had just read in a novel lent me by Mrs Patterson, that there are “two sorts of things you should never grieve at; those you can help, and those you cannot help.” this philosophy pleased me so much that I determined that very evening to commence the practice of it.

We arrived here this morning to an eleven o clock breakfast [. . .] and have been busy ever since, unpacking and arranging. the chest of drawers is such a convenience that I no longer regret its being brought to from Monticello, especially as I hope we shall be able to worry Grandpapa into having more of them made. V. and myself intend to be very industrious during our short stay, as it seems fated that we shall never do any thing at home.

Give my love to Jane and thank her for having recommended the “Miser married” to me. the first half volume is insufferably stupid and dull, but the rest amused me a good deal; the character of Lady Winterdale is so well drawn that it redeems the whole book. V. and myself feel very much indebted to Mrs Patterson, for her kindness in lending us these books, we found them a great relief to the ennui of the journey; we got in so early in the evening, and loitered so long at the tiresome taverns, where we stopped to have the horses fed, that reading was a most valuable resource in during this these weary hours. of [. . .].

I have thought a good deal of your coming out to the carriage the damp raw day we left home, and am very much afraid you took cold; I wish I could hear my dear Mother; for I shall be anxious untill I do. have you remembered to move the gun-powder from the hearth? no harm can ever be done by precaution, and I think it is always well to consult not only probabilities, but bare possibilities.

Virginia and myself take this opportunity to enter our protest against any name that may be given to the boy in our absence, unless it be Archibald or Lucius Cary—dear little Patsy was unwell the day we dined at Warren, but that did not prevent her from looking as sweet and pretty as usual. Margaret looked uncommonly well. she certainly has a most extraordinary countenance for a child—there is a mixture of intelligence and oddity that I never saw in any one else, and if she is not something out of the common way, I will give up all my claims to skill in physiognomy.

Tell Cornelia that Mr Hill (the gentleman with the diamond beetle) is courting Jane Braddick—I fear this would be no great match, and she had better submit to her sister’s tyranny for a little while longer, than change it for a worse—also—Miss Stratten (Mr Nivison’s Miss Stratten) is actually married to Mr Wilson, the member of legislature, whom she may remember always neatly dressed and powdered, and talking of Philadelphia ’till even I got weary of the subject—if she does not know him by these tokens, bid her remember him as one of the alligators, whose open mouths and furious gestures, gave me such reasonable alarm at the governer's party—to do him justice he was the most like a civilized creature of the three—the others being Mr Rives and Mr Thompson—tell her moreover that Miss Betsy Fisher admires me above all earthly things, and that Mrs Scotts daughter is already a second Helen, destined to fire a second Troy, but whether this will be Richmond or some town of greater note, is still “enveloped in the coils of futurity ” (W. Somervall) in spirit.)

Will you my dear Mother, desire Elizabeth to ask Aunt Hackley in my name for some volumes of the Experimentas de Sensibilidad—I think it would be well to return by this opportunity, such Spanish books as we do not want, Alexo for example which is too stupid to be read, and has not even the recommendation of being easy I feel ashamed to borrow more whilst we have so many—

I left cambric for one pair of sleeves, which Sally can cut out by the paper pattern, taking care to make them longer & larger, and besides this to allow for eight narrow tucks, which she must put in them as they are for my tucked frock which I brought have with me—she knows how to frill them.—if muslin and cambric of a proper sort can be got, I wish my cambric frock with the pointed flounce, to have a new plain flounce, and new sleeves with three puffings like Cornelia’s stuff—the cambric dress with the striped flounce to have new plain sleeves with straps to them, and the flounce ripped off—when she has done this and it is not a week's work; she may begin the tail of my striped muslin—which she is to trim with three puffings, in the manner of Cornelia’s sleeves, set on above the hem the width of which she will know by a pin stuck in it—I hope she will work steadily for otherwise when I get home I shall meet a great deal of company & have no [. . .] clothes to wear—

I began as usual my dear Mother by telling you I had nothing to say, and find as usual, that neither my time [. . .] or paper would will allow me to say every thing I wish—but I must not forget to warn Cornelia that she is not to let that poetry of Mr M’s run the gauntlet, altho’ I let Elizabeth and herself copy it—I do not think it would be proper, to subject to criticism what was merely a “piece de circonstance” and did extremely well as such—she must not forget to sow Mr Smith’s seed which is in my writing desk—& to plant my two beans in my writing table. * if Mr Trist understands my hint, and brings any of his vellum paper, pray take great care of it for it will be a great acquisition—I do not think I can get any of that width else where—I shall not fail to do Uncle Tom’s business when I go to Lynchburg—

Adieu my dear mother—if you have patience to get through such a mass of uninteresting matter it will “add another rose to your crown”. I send back a little trunk with my stuff frock (which will be of no farther use, as I shall travel home in a gingham) there is no time to make cake for Tim—give my love to the girls & boys, & to Papa if he is still with you most particularly—tell Mary she is enquired after by Aunt Hannah—& by name—for which she must feel due joy any and gratitude—once more adieu my dearest mother and believe me with the truest affection your daughter—

Sally must make the tucked sleeves of the coarsest piece of [c]ambric—

Do throw this letter in the fire.

* I do not mean that the beans are to be planted actually planted in the writing table, but that she will find them there among the wafers—upon looking over my letter I concieved this explanation necessary, for from my manner of expressing myself and from the quantity of dirt in the drawer, it would be very natural to suppose I meant to turn it into a flower garden.