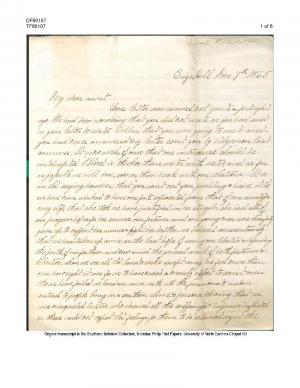

Sarah N. Randolph to Cornelia J. Randolph

| My dear aunt, | Edge Hill Dec. 7th 1865 |

Your letter was received not quite a fortnight ago. We had been wondering that you did not write, as you had said in your letter to sister Ellen that you were going to write and you had never answered my letter sent you by Algernon last summer. It is no wish of ours that our intercourse should be interrupted. “Blood is thicker than water” with us too, and as far as possible we will bear, sooner than break with our relations. It is an old saying, however, that “you cant eat your pudding & have it too,” we have never wished to have our fate separated from that of our countrys—every step that she took we have justified—in her struggles she had all of our prayers & hopes for her success—our fortunes and our young men were cheerfully given up to support her armies & fight her battles—we believed conscientiously that we had taken up arms as the last hope of saving our liberties & defending the faith of our fathers—and now amid the general wreck of both fortunes & liberties—when we see all old landmarks swept away we feel more than ever how right it was for us to have made a manly effort to resist, even tho we have failed—we loved our cause with all the passionate ardour normal to people living in a southern clime & persons believing that we were misguided traitors who deserved all the sufferings & injuries inflicted on them us could not expect old feelings for them to be retained—regret the estrangement however much we may. If I had a brother who thought our subjugation right, I should feel myself more closely drawn to any stranger with southern feelings than to him—and this is the feeling which we consider it our most sacred duty to keep up and which from morning until night we are instilling into the hearts of the children of the house—in their nursery tales & rhymes “Yankee” has taken the place of ogres & wicked fairies and all that is vile & despicable—And now my dear aunt that I have shown you the intensity of our feeling I shall never again introduce this sad subject and only add that if you could hear father talk you would think me mild in comparison with the bitterness of his feelings—he has no hopes for the future, but except for our failure. no regrets for the past—You are not to think now, that we have any other than affectionate feelings for any of you, for we have loved you too long and too well to think of you in any other way than as our dear, good aunts.

I cant tell you what a constant source of trouble and annoyance fathers inability to send you any money has been to us all this whole fall—we had [. . .] hoped certainly to send you part of your interest at least—but having to restock the plantation, being obliged to have repairing done after the wear & tear of four years and to pay wages now to our servants swallows up every cent & leaves us scarcely enough to furnish us with the bare necessaries of life. Father hopes, however, in a week or two to be able to send you one or two hundred dollars—You said cousin Algernon had told you that your money was safe—it is safe because because father of course considers himself bound to you for it—but every investment which he had in stocks &c was lost and all that we have left in the world is the plantation. Aunt Mary has three or four hundred dollars in an Insurance company in Ch:ville which though unsaleable now is good and the company expects to pay a dividend in July next. After the pinch of this year is over I hope you will never again suffer as you now do from the delay in receiving your income—Farming here is considered an experiment now under this new regime, yet there is no repining and every one is determined to give it a fair trial. Now that the excitement of the past four years is over, and for us, all but honour is lost, the men of the country can only find comfort in hard work & they have set to work to rebuild their shattered fortunes with an energy & determination which redounds as much to their honour now as their gallantry did in time of War. Lewis lives at home and has charge of the plantation under father—he is constant & untiring in his energy and we already begin to see the good effects of his good management—The life he leads, though, is utterly & entirely distasteful to him, and if father were ten years younger I do not think any power could keep him in this country. He and Mother are constantly wishing they could move out of the country—but I love my home & state too dearly for that, and things will have to be worse for us than they now are even, for me to be willing to give them up—I am sorry you have so much trouble with your servants—how different from our faithful blacks who are so devoted to us that we cannot get rid of as many of them as we ought. They have never been more respectful or [. . .] willing to work than they now are—Anderson’s health has broken down entirely and he is now a confirmed invalid and at times a great sufferer—Sidney & her family are to be moved out of the yard and will live in a house just built for them on the top of the mountain—Our greatest trouble is in [. . .] easing off the large families—Old Minerva died several years before the War and Burwell the second year of the War—we were all so sorry that we did not think at the time of having him buried at Monticello. The old place is in the hands of the overseer who Levy left there—I believe it is undecided whether it belongs to the U.S. Govt or to Levy’s brother. I got from there that little alabaster lamp & a mirror just the size & shape of the arched top of the one in the dining room here—Wilson has moved down to his farm to live where he has fitted up a very humble dwelling for himself & family. In spite of my protestations to the contrary they will not call the place “Chapel Ridge.”

Tom lives along as soberly & quietly at Shadwell as he used to do—he has all of his children with him but George—the youngest and Jeff Taylor lives there & teaches them. We like his wife very much, but of course his quick marriage was a very great shock to us sister Ellen paid us a long visit this fall—I wish you could see her boy—Jefferson—he is a fine looking little fellow & so sweet & attractive. They have had half of the house fitted up at Brandon and are living there. We have not seen sister Maria for over two years—we are hoping, however, to have a visit from her some time soon—Jane & her four children are spending the winter with us—Mr Kean has resumed his practice in Lynchburg & Jane expects to join him in June—Willy has a place in a commission house in Richmond—all the fall he has been drumming for his house—Roane Ruffin has the management of his father’s farm as Lewis has of this one—Mr Ruffin’s health is very feeble—You would never know Roane he has grown so—he is almost as tall as his grandpapa—he is a very sweet fellow—Bennett lives at home—he is engaged to a Miss Lucy Colston of Berkley County—not at all good looking but a nice lady like girl—she was well off before the War but now they are both so poor they cant get married—Lewis Carter is Engaged to Miss Lou Hubard—Isa’s sister-in-law. He poor fellow has a right hard time—his father will not let him assist him on the farm & he has little or no practice—Uncle Ben considers he is entirely ruined and he makes no effort to adapt himself to the new state of things but lets the plantation, negroes & everything else go on as best they may—You can easily imagine how violent he is in his talk & feelings now—His health was wretched during the summer, but is quite good now. I wish I could think of my darling uncle George’s health as you do. How do you account for the hemorrhages he has if you think his lungs are sound—A letter received from uncle Coolidge two weeks ago tells us of one he had just had and a letter to me from aunt Mary just received to-day gives very poor accounts of him—she seems exceedingly desponding about him. We were all very sorry for cousin Pattie & sympathised with her in her affliction. M Burke seemed so much distressed when he was here—we were so glad to see him once more—You did not mention cousin Jeff & Ellen in your letter. Give our love to them and tell them we often think with pleasure of their sweet little visit to us—I am so sorry to hear that aunt Trist still suffers so much with her eyes. I had hoped they gave her no trouble now—Sister Ellen has little or no use of hers—Aunt Mary I hope has gotten quite well again—You all must have had a time this summer and with Annie to nurse through that trotious illness too. Father was very glad to get uncle Trist’s letter about the grapes—he is anxious to set out a vinyard. I am going to write to the man to know what deduction in price of plants he will make for vineyards and then if I can scrape money enough together I shall get some plants. I should like to get enough for an acre but cant aspire that I high yet awhile. I want to have a vineyard just outside of the yard to the left of the western gate, but I do not know how the western exposure will suit—I wish you had in your empty henhouse some of the thirty hens that I have who eat their heads off & never seem to think it at all encumbent on them to lay any eggs. Sister Carrie has your little henhouse and I have sister Ellen’s—Eliza & Cary have grown quite out of your knowledge, I expect. Eliza is on a visit to her father now—She is a very sweet good child—I teach her, and Lucy Mason is coming up soon to join her in her lessons & spend some months with us. Cary is a fine, manly little fellow who runs from morning ’till night (except when he is in school) and rides every horse on the place—I heard his grandpapa scolding him the other day because his uncle Lewis had lent him his horse and he had raced the poor creature three miles & back without giving him time to draw a long breath. He has a smack of the Ruffin ugliness, but a very sweet countenance and a figure & carriage more exactly like his dear Mother’s than you would ever believe it possible that a little boy’s could be like a grown woman’s. We have never grown reconciled to our darling little Johnny’s death, and not even the two years of the excitement, suffering & confusion of War which followed has been able to drown of our tender grief for him—Each new stage of Cary’s mental & physical development serves but revive our love for him & the bitterness of his loss to us. Except by the loss of ever dear cause I have never seen father so crushed by any blow as he was by that child’s death. I so often think of the gentle, kind way in which aunt Mary & yourself nursed them when they were babies. I do not think father has grown much older in looks in the past few years—he is nothing like so feeble looking as uncle Ben. He has a funny affection of the knee. In a certain position that the limb is sometimes thrown into, the small bone of the leg slips out of place & for the few minutes seconds which it is out of joint it gives him great pain, but we all know now the peculiar twist to give his foot to get it back into place and whenever he screams out, as he always does whenever it happens, some one runs to him & seizing his foot sends the bone back into its place with quite an audible pop from it as it slips back—Mother got a letter from cousin Mary Page last week, which if I can find I will enclose to you. Cousin Francis has lost almost every thing in the world which he had—At Aunt Eppes’ death two years ago he got quite a handsome little property here in Virginia which with the folly almost of a crazy man he sold last Spring & invested in Confederate Bonds. All send you all much love. Father said this morning he was going to write to you soon—but Mother says as his letter will be nothing but a furious political document he shall not do it. She spoke of writing to uncle Trist. Goodbye my dear aunt. write often Your aff. niece