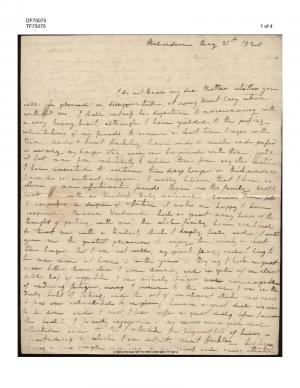

Ellen W. Randolph (Coolidge) to Martha Jefferson Randolph

| Belvidera May 31st 1820 |

I do not know my dear Mother whether you will p be pleased or disappointed, at seeing Aunt Cary return without me, I shall witness her departure to morrow morning with a very heavy heart, although I have yielded to the pressing solicitations of my friends to remain a short time longer with them. Uncle & Aunt Hackley have said so much and pressed so warmly my longer stay, every one has joined with them, until at last more from imbecility to refuse than from any other motive I have consented to continue ten days longer in Richmond, as I can do so without expence—I really believe that I have no where no more affectionate friends than in this family. Aunt H. treats me with a kindness truly maternal—Cousin Jane feels & expresses a degree of affection it makes me happy to have inspired; Maria Woodward shed a great many tears at the thought of parting with me, the whole family have combined to treat me with a kindness which I deeply feel, and it would give me the greatest pleasure to enjoy their society a short time longer; but I am not well, my spirits flag, and I long to be once more at home & with you—they say I look a great deal better than when I came down, and in spite of an almost total loss of appetite, I am certainly stronger [. . .] and more capable of enduring fatigue, owing I presume to the exercise I am in the daily habit of taking, and the sort of excitement which new scenes & faces are calculated to inspire; however a great deal remains to be done and I must, I fear, suffer a great deal, before I recover the health I formerly enjoyed—my nerves are a good deal affected; and to this I attribute the frequent fits of heavy-heartedness to which I am subject. Aunt Hackley has been trying a few simple remedies, for my relief, and every attention which it was possible for any one to pay she has lavished upon me, and in a manner so truly affectionate as to double the value of her kindness—Uncle Hackley has quite won my heart, by his attentions and the interest he appears to take in me, but in spite of all this I had rather go home for I am just in that state when man delights not me nor woman either I my tastes are fading and I should almost doubt my own identity if it were not for certain feelings or rather habits of thought which are too surely my own, and by which I recognize myself—for the rest I have not opened a book since I came to Richmond nor felt the smallest inclination to do so, although I have had several hours of listless vacuity—the piano and a fine one is before my eyes, I look at it and forget to touch it. now and then I have thought of Sully and regretted that I was losing so much time from drawing, but even this is momentary and I relapse into indifference. it is better for me to be at home for there the influence of habit prevails, and I engage in my accustomed occupations exactly because they are accustomed—but here there is no such association, and almost my only employment is consists in coaxing on the slender wardrobe I brought with me to make it suffice for my wants, and this was another objection to my staying, which Aunt H. overruled, or rather would not admit the existence of—say nothing to Aunt C. of these my complainings, they have never been made to her, she has seen me apparently cheerful or at least be tranquil, and will no doubt make a favorable report of my looks & spirits.—she will also tell you my various arrangements for getting up, or rather the arrangements which have been made for me, for I have listened passively and acquiesced after a good deal of resistance, which was overpowered rather by my own languor, than by any great wish to remain or any conviction that I was right in doing so.—I am almost incapable of the exertion of thought or any species of moral calculation I have one consolatory reflection in the midst of the self-reproaches by which in spite of my apathy, I am assailed at the thought, of yielding to the solicitations of my friends here in preference to the more natural wish of returning to you—my stay, will enable Aunt Cary to take Ann up with her from whom she has been separated the whole winter. the child is passionately desirous of returning with her mother and cryed bitterly at the thought of remaining—she said to me in the most imploring voice, Cousin Ellen my clothes are all packed up, if I can but go with Mama. Mrs Cary (the old lady) is anxious to gratify her darling and had I persisted in returning I should have dissatisfied all parties—add to this Aunt C. has added so much to her luggage that, I should of necessity be forced to leave much the greater part of my baggage and take with me only what was absolutely necessary—as it is, whether I go up with Mrs R. Cary; or with Uncle Hackley or Richard or both I shall have Phil and the cariole (which will be returned to Richmond in 5 or 6 days although at present lent out) to go up with me, and carry my trunks and band box.—

Aunt C — will give you an account of our adventures & misadventures—the scandal which was talked in consequence of our being too late at one of the parties, charitably attributed to airs and insolence—the passionate desire I felt to hear Mr Nicholas sing (the only anxious wish or desire of any kind I have experienced since my arrival in Richmond) and his childish capricious conduct, which effectually destroyed the admiration I was inclined to feel for him, giving me a double disappointment, first in my anticipated pleasure and t also in the estimate I had formed of his character—Miss Braddick mentioned to him the desire I felt to hear him sing alone, he immediately came forward in the frankest manner, expressed the pleasure it would give him to oblige me, regretted that the [. . .] of a large crouded party at which we met the next evening was unfavorable to my the wish I was pleased to express; came in the next morning to Mrs Butler’ss where I was expressly to wait upon me, and say that Col Peyton talked of making up a party for me in a few evenings which would be small and select when he could sing to advantage, and added that as I was to leave town so soon (I never determined to remain until to day this evening) he was going to see the Col. to hurry him and put him up to giving his party at once for fear of disappointment. the evening arrived I went early full of hope and joyful anticipation—the gentleman entered a few moments after full of smiles and graces and spirits conversed in the most easy and animated manner for a short time, was called on to favor the company with a song, declared himself languid & out of spirits rolled his eyes, pouted his pretty lip, submitted to urgent entreaties in which I scorned to join, clapped his white hand to his eyes, [. . .] and when asked again his reason for refusing, replied he could not tell, he felt inexpressibly picked up his hat and marched off in all the triumph of a spoiled capricious child, proud of having it in his power to disappoint and disoblige a whole company—some one charitably concluded he must be unwell, to which his intimate friends the Gibbons replied oh no! it is nothing but an air —he shall not again [. . .] play of his airs upon me thank heaven, it was Miss Braddick who proferred the request, and I have not the mortification of [. . .] feeling myself to having have been guilty of much undue condescension—but I never was in a greater rage, it completely roused me from my sleep of apathy; the fascinating tones which I have several times partially heard mingled with the shrill discordant screams of female singers, often overpowered by then fashionable squallers, but then again rising in a stream of melody so rich and deep as to hear every thing before it, to be lost the moment after—I have been completely in the state of Tantalus, and almost wished I had never heard the silver sounds which came at intervals to haunt my imagination succeeded by the short shrill shreik which even in fancy, and in the solitude of my own chamber made me start & clap my hands to my ears—and then when I had promised myself an ample reward for all these sufferings to be disappointed by the fickleness and caprice of the little wretch. it was too bad; when I am most under the influence of torpor, most difficult to rouse, then one favorite desire appears to acquire strength from the absence of others, and I can awake to disappointment and resentment—

Adieu my dearest mother, write to me soon, for I certainly shall not remain here more than ten days at farthest, take care of your precious health, love to all the family and to you yourself the assurance of a devotion no language can express—