David M. Randolph (1798–1825) to Nicholas P. Trist

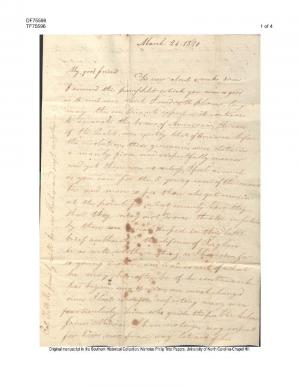

| My good friend | March 24. 1820 |

’Tis now about 4 weeks since I received the pamphlets which you were so good as to send me, which I read with pleasure, long may the sentiments expressed it in continue to animate the bosoms of Americans, the case of the Cadets was exactly that of America before the revolution, their grievances were stated in a manly firm and respectfully manner and yet there was no redress, I feel as much as you can for the 5 young men of the committee and more so for those who yet remain at the point for what security have they that they may not be worse thraten in future by those wr rascals dressed in their “little brief authority.” the defence of Ragland is as well written a thing as I have seen, for so young a man, and is an ernest of what he may hereafter be if he continues as he has begun, my opinions are much changed since I last saw you respecting many men [. . .] particularly him who guides the public helm James Monroe, I have no longer any respect for him, not from any late act of his but from his treatment to Alexander Hamilton and the manner in which he backed out of that scrape, I know that you respect him and do not whish to alter your mind but state the circumstance to justify any incongruity which may appear in my conduct or conversation with respect to him, The opinion of my good friend J. G. Mosby that no man can be [. . .] in public life and remain honest is I believe too true, by honesty I mean that he can’t at all times speak what he thinks an consequently must dissimulate and from that to he passes to other things worse, my Idea that the quantum of honesty in these days is less than it ever was, scarcely a day passes but I hear that some man who has heretofore stood high with the world has been guilty of some rascally act men who were old and whose sense of honour hah been blunted by collision with the world might be expected to do a mean action but when young men just springing in to life begin with them, in my opinion it is a sign of a corrupt world and much I fear that in those cases a bad begining will1 not made a good end such is now the state of things, Oh my friend may we continue as I hope we have begun in the right way and may it never be said of us Mene Mene tekel euphrasin, to change the subject; had I not been fortified against the attacks of cupid I should have fallen a victim to love this winter, you I suppose still remain you affection for Virginia, need I repeat to you that if that event ever takes place that I of all others shall not be the least pleased, indeed, my dear fellow in the gloomy futurity before me the hope of pleasure or gratification arrises more from the expectation of seeing my friends happy than any real good that can befall myself in propria personæ persona. What was the reason that the Seldens were not liked at Bentivar? Charles I think has a fine countenance as I ever saw and John seems to be a good fellow enough, not overburthened with talents though, they are at [. . .] with Browse. by the bye Browse is a sad fellow two letters have I written to him and devil a word have I received in reply My poor Mocking bird that I intended for Cornelia died not long after I wrote you my last letter. I liked to have died last summer of the bilious fever the world would have lost a good man if I had, God bless you and keep you in health

Col. T. M. Rs family will live in Richmond next winter.

Mene mene tekel upharsin [euphrasin] were the words written by a bodiless hand on the wall at Belshazzar’s feast in the Bible, Dan. 5:26–8. The word tekel is rendered in English as “thou art weighed in the balances, and art found wanting,” and is sometimes taken as the meaning for the entire phrase (OED).