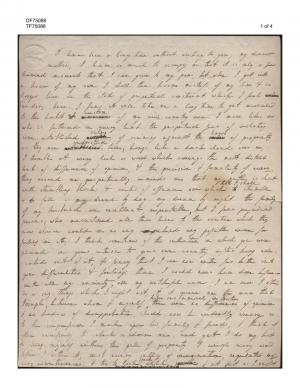

Ellen W. Randolph Coolidge to Martha Jefferson Randolph

| [Aug. 1825] |

I have been a long time without writing to you, my dearest mother, I have so much to occupy me that it is only a few hurried moments that I can give to my pen, but when I get into a house of my own I shall then become mistress of my time & no longer live in the state of perpetual constraint which I feel under under, here. I fear it will take me a long time to get reconciled to the habits & manners customs of my new country-men. I move like one who is fettered in every limb. the perpetual fear of violating some established custom rule, of sinning against the rules laws of propriety as they are established understood here, hangs like a dark cloud over me, I tremble at every look or word which conveys the most distant hint of difference of opinion, & the precision & formality of every thing around me perpetually reminds me that my path is beset with stumbling blocks & rocks of offence over which to that I shall stumble or to fall is [. . .] my dread by day, my dream by night. the family of my husband are excellent, respectable, but I fear prejudiced persons, who accustomed all their lives to the routine which they now observe could in no way comprehend1 any possible excuse for failing in it; I think sometimes of the situation in which you were placed on your return to your own country after being educated out of it, & fancy that I can now enter far better into your difficulties & feelings than I could ever have done before.—with all my anxiety, all my watchful care, I am sure I often do or say things which I ought not, & it grieves me the more that Joseph, between whom & myself before our arrival in Boston there were no differences of opinion & no shadow of disapprobation, should now be evidently uneasy as to the impression I make upon his family & friends, & think it often necessary to check or advise me. and yet I do my best to bring myself within the pale of propriety. I weigh every word before I utter it, curb every sally of imagination, regulate my very countenance, & try to look, speak walk, speak & sit just as I ought to do; but then I have twice refused to see company because my head ached so that I could not hold it up. I am often not ready for breakfast because Joseph will not rise & I cannot learn to rise get up & dress before him in cold blood, although in the hurry of travelling I was forced to do it. then I run down stairs in a hurry & leave my clothes scattered about the room, I breakfast in one of my colored wrappers because it is the only dress I can put on in haste & without assistance. I cannot eat any kind of fish, pork is my abhorrence & pudding makes me sick, & these three articles are the staples of a new England table, & although I do ample justice to the fine fowls, excellent vegetables & good fruits which ever form a part of every repast yet I do believe it is looked upon as pure caprice my disinclination to the other popular articles, I have mentioned. with regard to the society at large, no particular attentions are paid me, nobody seems inclined to seek my acquaintance except Mrs Ticknor & Mrs Derby, who by the way is a lovely elegant creature, & I have no particular reason to congratulate myself on Boston hospitality although I have [. . .] none to complain of neglect. in Joseph’s family, his father is a frank generous man, full of good feeling & warm affections, but firmly convinced that there is nothing on earth to equal or compare with New England, of which Massachusetts is the first State & Boston the first city. Mrs Coolidge is mild, subdued, pious & the most conscientious of beings, but tight-laced in all her ideas, & although finding no fault with any one, yet often disapproving in silence, & letting her disapprobation appear, quietly & calmly but fixedly. Elizabeth is gentle, amiable & kind, but not free from prejudice; she is a little deaf but not enough so to disturb the pleasure of conversing with her, whereas Mrs Coolidge is so much so, as to affect the modulation of her voice, & I am often thrown into a panic by not understanding a word she says to me, & running the risk of making a mal-apropos answer, which, (as her family, accustomed to her tones, find not difficulty in comprehending her,) she might be displeased at. Mr Swett is a merchant who thinks of nothing but his business & regards with cold disapprobation all tastes & inclinations not tallying with his own. Thomas loves neither his brother nor his brother’s wife, & takes no pains to feign an affection he does not feel. there is not ‘le plus leger teint’ of literature in the whole any of the family, books are never spoken of, & reading, I suspect, considered as a waste of time. I have been treated with so much real kindness that it grieves me to think how little congeniality there is between me & any one member of the household, & how impossible it is they should ever learn really to love me. they will do every thing in their power to serve & oblige me, but can never take pleasure in my society, or value me for qualities which in their eyes have no value, whilst the want of method & precision in small things and of a strict observance of forms to which I am unused, will impress them with an idea of outlandishness & non-conformity, most unfavorable to their esteem for me. I cannot tell you how these things harrass me especially as Joseph is fully impressed with the idea that his family are impeccable & infallible, (an opinion which they by no means reciprocate) & when he finds himself differing from them, says with a sigh that he has been spoiled by his residence in Europe. I shall be delighted when we get to housekeeping, for now I feel as if snares & pitfalls were every where under my feet, or rather like one submitting to the fiery ordeal & walking blindfold & bare-foot over red hot plough-shares. my spirits too are often depressed by homesickness, yet with all these troubles I have never regretted my marriage, & look forward to the time when I shall be far happier & better-satisfied than I am now. my situation if not brilliant will be, I hope, easy & comfortable, & when my heart gets so far weaned from my native home as to enable me to find interest in that of my adoption, I shall then enjoy the pleasures it may afford me. my affections to those I have left behind must ever continue the same, but I trust I shall not always care as little about those around me, as I do now. with the single exception of my husband, I have now no object of interest. I see Mrs Greenwood as often as I can & find her always kind & affectionate, but he is a little stiff, & I have not yet got well acquainted with him, but he is a most excellent man. there is a little girl of the name of Perkins who pleases me much, & strikes me as having less of that extreme & rigid decorum which every body else seems to entrench themselves in. she says what she thinks, & feels for & sympathizes with the unfortunates who are used to do the same, and I can speak more freely to her than to almost any one. Francis Grey is likewise one of my favorites.—I have written a long discontented kind of letter my dear mother, but if I write to you it must be a transcript of my feelings, and you know me too well not to enter into & understand them without making yourself more unease than the case requires. there is one thing, very certain, if I am ever happy or deserving to be so, it is to you alone that I shall owe it; I have no principle either of happiness or virtue which you have not given me, whilst my faults are all my own. adieu then my beloved mother, little have I ever done or can I ever do to discharge the weight of obligation & gratitude I am under to you, but I can love you better than all earthly things, & feel that to permit any sentiment to rival the one I have for you, would be injustice & ingratitude. none can ever be to me what you have been & none can ever claim precedence over you in the devoted love of your own daughter.

(love to all, & burn this treasonable letter.)