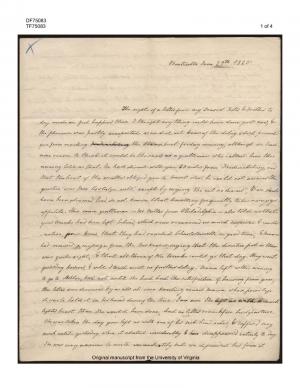

Virginia J. Randolph Trist to Ellen W. Randolph Coolidge

| Monticello June 27th 1825 |

The sight of a letter from my Dearest Sister & brother to day made me feel happier than I thought any thing could have done just now, & the pleasure was partly unexpected as we did not know of the delay which prevented you from reaching Fredericksburg the Steam boat friday evening, although we had some reason to think it would be the case as a gentleman who called here this morning told us that he had dined with you 20 miles from Fredericksburg, and that the heat of the weather obliged you to travel slow. he could not answer the question “was Mrs. Coolidge well” except by saying “She eat no dinner”, & we should have been alarmed had we not known that travelling frequently takes away yr. appetite. this same gentleman—Mr. Miller from Philadelphia—also told us that your trunks had been left behind, which news occasioned us much surprize & consternation, as for we knew that they had reached Charlottesville in good time, & Mama had received a message from the bar keeper saying that the direction put on them was quite right, & that all three of the trunks could go that day. they went yesterday however, & will I trust meet no further delay. Mama left us this evening to go to Ashton, but not until she had had the satisfaction of hearing from you, the letter was devoured by us all at once kneeling round Mama whose privilege it was to hold it in her hand during the time. I am sure She [. . .] left us with a much lighter heart than She would have done, had no letter come before her departure. She was taken the day you left us with one of her sick head-aches, & suffer’d very much until yesterday, when it abated considerably & has disappeared entirely to day. She was very anxious to write immediately but we dissuaded her from it. fearing that it would occasion a return of her head ache. there is no cause for your feeling the slightest uneasiness about her dearest Sister Ellen, nor must you allow yourself to feel great disappointment, [. . .] for there is still time for her to write to you in New York, & nothing can prevent her doing so but Elizabeths sickness. Grandpapa’s health is steadily improving, & he told Dr Dunglison when he came last to see him that he was quite as well as he was this time last year. but I fear he misses you sadly every evening when he takes his seat in one of the campeachy chairs, & he looks so solitary & the empty chair on the opposite side of the door is such a melancholy sight to us all, that one or the other of us is sure to go & occupy it, though we cannot possibly fill the vacancy you have left in his society. I can not add to your own distress at parting with us, by saying what a loss you are dearest Sister, you must know it, for you know what a valuable friend, and tender daughter & sister you have made. me you have counsel’d wisely, comforted in distress, smoothed the difficulties which crossed my path in learning, & excited the desire which daily grows upon me to resemble you in all that I can. your figure is constantly before me in every part of the house, & I almost fancy when I go out of it that I shall see you in some of your favourite haunts. what would I not give to see you, to hear the sound of your voice, oncemore to feel you [. . .] encircled by my arms. nevertheless I wish nothing undone which has occasioned this separation, I am not so selfish as to wish to see your happiness sacrificed to save me a sacrifice, & I love Mr. Coolidge dearly, & believe he can do more to make you happy than any one in the world besides. I do not feel jealous of him either, because my own heart shows me that perfect love for our husbands & sisters may exist together, & never clash one with the other. you will have many things to occupy both your thoughts & time now, that you have not had hitherto, but when ever my turn comes to engross you let it be for ever so short a time, write to me as you would speak if we were together my own fondly loved sister, think nothing which concerns you too trivial to interest me, & continue to me the comfort of your advice in my future conduct in life. none but Mama knows me so well, is so capable of directing me, and feels a greater interest in me—& no one I may safely add has the same influence over me, & ever has had, except herself. be then what you ever have been to me, dear dear Sister & I ask no more. I will learn to console my self for the loss of your society during the greater part of the year, by thinking how inestimable the value of it will be during the time that you will annually spend here.

We are all trying to remember & execute the slightest of your wishes expressed about the arrangement [. . .] of your things at home. I have nailed the curtain before your books to protect them from [. . .] harm, & I think we shall show the wisdom of a Daniel in judging what to send you & what to retain ourself ourselves of your effects. every thing antiquated in your service, ranks with the 100,000$ prizes in the lottery, & tod[ay] I hugged to my heart a little long necked bottle which I remember long to have seen in your possession & which Mama resigned to me tho’ a part of your legacy to her medicine chest. It is getting quite dark, & I have already told a story to avoid the interruption which a visit from Mrs. Higginbotham & Miss Garrigues would otherwise have occasioned in to my letter this evening, & now I am half ashamed to send so ill favoured an epistle to the hands of a lady in the Metropolis of New York. but you may easily hide my shame [. . .] and the letter in your reticule, & look at its contents in private. Nicholas sends a great deal of love to Mr. Coolidge & yourself—he returned to me sick the evening after he parted with you. I know Mr. Coolidge will not quarrel at my sending him a kiss by you, nor should I insinuate that he would receive if it from my lips unwillingly considering my claim to a sister’s privileges—Adieu I can no longer see atall & must cease the attempt to write longer believe me too devotedly attached to you for my feeble langage to express the hundredth part of what I feel.

I wish you to inform me whether drips of the kind Mrs Madison has, in wh. the water passed thro sponge, charcoal & sand, are to be had in Boston—& what they cost.—