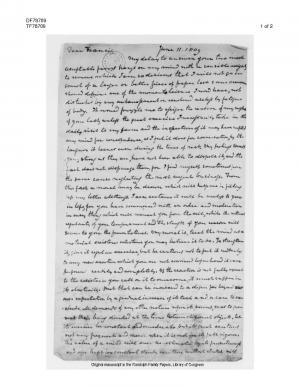

Thomas Mann Randolph to Francis W. Gilmer

| Dear Francis, | June 11. 1809 |

My delay to answer your two most acceptable favors hangs on my mind with a sensible weight, to remove which I am so desirous that I will not go in search of a larger or better piece of paper lest some occurence should deprive me of the moments leisure I now have, not disturbed by any embarassment or rendered useless by fatigue of body. It would puzzle me to assign the reason of my neglect of your last, unless the great exercise I necessarily take in the daily visit to my farm and the inspection of it may have unfited my mind for correspondence, as I feel it does for conversation, by the languor it leaves even during the time of rest. My feelings towards you, strong as they are, have not been able to dispell it, and the fact does not disparage them, for I find myself sometimes from the same cause neglecting the most urgent business. From this fact a moral may be drawn which will help me in filling up my letter allthough I am certain it will be useless to you in life, for you have commenced with an order and moderation in every thing which will warrant you from the evil, while the natural regularity of your temperament and the strength of your reason will secure to you the preventatives. My moral is, treat the mind as a material existence whatever you may believe it to be. To strengthen it, give it regular exercise, but be cautious not to put it suddenly to any new exertion which you are not convinced beforehand it can perform, readily and completely. If the reaction is not fully equal to the resistance you call on it to overcome, it must suffer in its elasticity. But that can be increased to a degree far beyond [. . .] our own expectation by a gradual increase of its task and a care to exclude all demands of any other nature upon its powers, so as to prevent their being divided at the time between different objects. Let its exercise be constant and moderate but its great exertions not very frequent and never when it is not in its full vigour. The value of a mind will ever be estimated by its productiveness and one kept in constant steady exertion without stretch will in proportion that is to its natural powers, produce more than one held commonly in idleness but sometimes put abruptly to great exertion, in the degree that the body of the artizan is more productive than that of the hunter. But to connect my moral completely with the fact let me observe that the leisure of the body when preserved in proper health by attention to air, exercise diet & rest is in fact the strength of the mind while the toil of the former is its weakness. The ancient philosophers who were much nearer to nature than we are I suspect, considered the rest of the body essential to the culture of the mind and they remained in the shade of their gardens neither exposing it to the toils of Exercise or digestion.