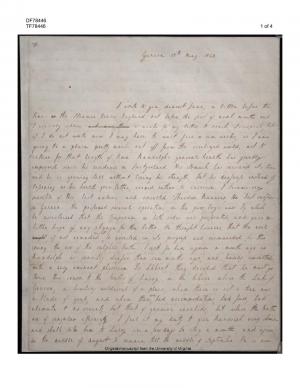

Ellen W. Randolph Coolidge to Jane H. Nicholas Randolph

| Geneva 17th May. 1843. |

I write to you, dearest Jane, a little before the time; as the Steamer leaves England not before the first of next month and I usually allow not more than a week for my letter to reach Liverpool, but if I do not write now I may have to wait five or six weeks, as I am going to a place pretty much cut off from the civilized world, not to return for that length of time. Randolph’s general health has greatly improved since his residence in Switzerland. His stomach has recovered it’s tone and he is growing tall without losing his strength, but his deafness instead of lessening as his health grew better, seemed rather to increase. I became very sensible of this last autumn and consulted Theodore Maunoir, the best surgeon in Geneva. He performed several operations on the poor boy’s ears by which he ascertained that the tympanam on both sides was perforated, and gave me little hope of any change for the better. He thought however, that the evil might, if not remedied might be arrested in it’s progress and recommended for this spring the use of the sulphur bath. I sent for him again a month ago as Randolph is sensibly deafer than six months ago, and having consulted with a very eminent physician Dr Lébert, they decided that he must go twice this season to the Baths of Lavey, on the Rhone above the Lake of Geneva, a howling wilderness of a place, where there is not a tree nor a blade of grass, and where there are bad accommodations, bad fare, bad climate & no society but that of genuine invalids, but where the Baths are of singular efficacity efficacy. I feel it my duty to give Randolph every chance and shall take him to Lavey in a few days to stay a month, and again in the middle of August to remain till the middle of September. He is now so deaf as to be cut off from all general conversation—hears nothing unless spoken in his ear and is, I fear, for ever deprived of all hope of belonging to any of the learned professions, for which his natural cleverness so well adapted him. Maunoir told me that had he not been very intelligent & willing, his education would have failed altogether; as it is he is pretty well advanced. His temper & manners are sensibly affected. His countenance is anxious & melancholy and he has become suspicious & irritable. He passes his whole time in reading and rather shuns than seeks companionship. His voice is somewhat affected in its modulations but not disagreeably, and as his language is generally good and he speaks french & english fluently, he gets along tolerably well on ordinary occasions—He is much disfigured by a singular defect in his mouth which as it belongs to neither side of the house, I hope he may out grow. This is a projection of the upper jaw considerably beyond the lower, which is depressed. I am not afraid of tiring you, my dear Jane, with these details—I know the interest you take in this poor boy to whom you were so long as a mother, and who continues to speak of you all with great affection.

I have been so terribly disappointed at Mr Coolidge’s detention in Canton that I cannot get over it, and have formed no plans for the future, nor do I know when I shall return to America. Boston is no place for boys who have no male friend or relation to keep them from running to ruin. I have there neither father, brother, uncle nor even cousin who could aid me with advice & authority. Here at least my sons are safe, morally speaking.

I have just transferred my Twins to a school at Vevey in the Canton de Vaud about half a day from Geneva.

How I wish I could pass this summer in Virginia, dear Jane; I long to re-visit home, to see my native mountains, to breathe the fragrance of the yellow jessamine, hear the cry of the Whip-poor-will, and find myself once more in the midst of friends. I should so much enjoy talking over old young times with Jefferson & yourself, when, with us all, life was young & promised to be happy, and I wish much greatly to be better acquainted with your children; I can scarcely believe that Maria is a woman although my own not tall daughter is one to all intents & purposes, having actually entered her eighteenth year. When you mentioned in your letter that your mother was in her eightieth I refused for a moment to believe the possibility of such a thing—I saw her eight years ago and my recollection of her was a well-preserved matron of fifty five—I do not know how it is—I feel very old myself, and look very old, & am perfectly reconciled to both, but I cannot picture my friends as old. I shall be greatly disappointed if I find M my contemporary & girlish friend Margaret more than thirty—I think she cannot be past this age. Give a great deal of love to her and to your dear mother, whom may God spare to you many years to come! I am very glad to hear such good accounts of Ben and Sally and their dear little ones—and George whom I think of now as established beyond the mountains. I wish my letters from Havana were more cheering, but I fear that Virginia’s health is failing again [. . .]d that Nicholas is doomed to poverty and struggling. [. . .] Ask Jefferson, dear Jane, to pay this year’s interest of my money to Virginia. I believe of all my mother’s children now, she stands most in need of it. Septimia writes to me far more cheerfully (though my other sisters never utter any thing like a complaint) and I hope the Doctor is turning his talents and skill to a good account. He is I think, a very clever man and an excellent physician, and I hear the children are very sweet little creatures—but I intend to write a scolding letter to Septimia, who is losing all her American feelings and taking up the prejudices & one-sided way of thinking that girls married to foreigners often do. I would not that my daughter, (if she marries at all,) should marry any but one of her own countrymen, for the wealth of all the Indies. I have lived years enough abroad to come very decidedly to this conclusion; and this partly because I am convinced that in no country in the world are women so much respected or as in America—and that no where are they under such good influences as married women—for girls in Europe are better educated than with us; yet they Here, in Switzerland, the women are excellent in all essential points, though deficient in beauty & grace, but the men are selfish and stubborn and expect to be waited on by their wives, sisters & daughters, as if each one were a Sultan. I never saw such a set of sulky savages, and I am told that in Germany it is worse still. Here at least the women are educated, there they are kept in ignorance for fear a knowledge of anything but brewing & baking & stitching for their masters, should spoil them as house keepers and drudges. In France, notwithstanding all that has been said to the contrary, I believe the women are in fact worse treated by the men and the laws that any where else. Let your daughters, my dear Jane, rejoice in being Americans & let them all marry American husbands! God bless you. I think of you more than I can tell you. I know so well how to sympathise with and feel for you. Give my best love to Jefferson and all your children with many kisses to the dear little grandchildren. Ellen wrote last month to Maria and now sends her affectionate remembrances. Ever, dearest Jane, faithfully and affectionately