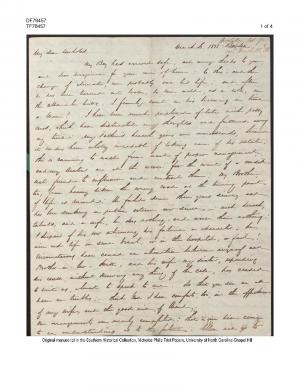

Joseph Coolidge to Nicholas P. Trist

| My dear Nicholas. | March 6. 1838: Boston |

My Boy has arrived safe, and many thanks to you, and dear Virginia, for your care of him: to this, and the change of climate, we probably owe his life; and, after he has been turned out loose, to run wild, as a colt, in the Albemarle hills, I firmly count on his becoming in time a Man! I have been much perplexed of late with petty cares, which have distracted my thoughts and frittered away my time: my Father’s health gives me uneasiness, because it renders him wholly incapable of taking care of his estate; this is running to waste from want of proper management; and my Sisters are all the worse for the want of a considerate friend to influence and controul them: My Brother, too, from having taken the wrong road at the turning point of life is ruined: He failed some three years since, and has been sinking in public esteem ever since—; with health, talents, and a wife, he does nothing—and worse than nothing: I despair of his ever retrieving his fortune or character: he will end life in some brawl, or in the hospital, or jail! Circumstances have caused an alienation between myself and Brother-in-law-Swett; and his wife my sister, espousing his cause, without knowing any thing of the case, has ceased to visit us, almost to speak to me. So that you see we all have our troubles;—thank God I have comforts, too, in the affection of my wife, and the good will of Heard;

Our arrangements are nearly completed; that is we have come to an understanding as to the future. Ellen will go to her Aunt Hackly: Randolph to Edgehill; the Twins to Cambridge, to the Revd Mr Newell, son in law and neighbour of Mr Wells; and Tom Jeff. will accompany us. I know of no plan so good as this, and my wife thinks so too; even if we were to remain at home, rich, and perfectly independant, I should feel such a temporary disposition of my children desireable, and so would their Mother, but the thought of parting from them is very painful to her; she says nothing, but I find her frequently in tears! I persevere however in recommending the course I have named, however, from an unhesitating conviction that it is best—first for them, as I have said, and secondly for their mother, whose health of body and mind requires, absolutely, rest and change: she is feeble, thin, nervous, and worn—; the sea, and a new world, will do more for her than medicine, and break up the recurrence of headaches which cause her great suffering and may finally destroy her—. I feel that she ought to go away, and also that I ought not to go without her. “It is not good for man to be alone,” and we have been already too much separated. I repeat, therefore, that she will accompany me to china—to remain. I know not how long, but perhaps not more than two years: and when we return perhaps it will may be by way of Egypt, & Europe! I shall look forward to being living near you, when I am here at home; perhaps something may occur to settle you in Phila, and in such case I would remove there: But it is not worth while to look forward so far, now.

I mentioned in a former letter that I wanted Septimia to accompany us to china—; this was that she might be a companion to E,—and in the hope that A. H. would offer to her, and be accepted. In this case we should have made a partie carrèe, and done very well for some time in the East [. . .]: Her singular folly has put an end to my hopes: As my letter will not reach her eye, I will add that her conduct creates but little surprise, being such as I always anticipated. She was right in her remark to Virginia—, I never did much like her—; and the strange course she has pursued since she has been a woman has confirmed the impressions made on me in her childhood. What think you of three engagements in three years? to men of whom she knew nothing, whom is was impossible she could respect? thank Heaven she did not take A. Hd she is wholly unworthy of him: but I will say no more.

We do not think of inviting either Ca or My to accompany us; they would neither of them suit us—, and the latter will be much happier with Virginia than any where else. entre nous she is, I think, devotedly attached to A. Hd and if he would give any encouragement would yield up every thing to follow him—, but her want of grace, youth, and loveliness chills and repels his imagination—: he has tried to love her, but cannot; respect and esteem her, he does—and appretiates her talents &c—. She has defects of temper wh. are undeniable, such as doggedness, disputatiousness, and something very like sullenness—: but she has also high principle and a good fine understanding. Could she have married young, her defects would have been corrected by a man she loved—; it is too late now. Have you ever noticed how little help she is—in sickness, in company, at times when her aid is required, and when another would see this and render it? There is an apparent selfishness about her which is unlovely. These things obscure her good qualities. Do not mistake me—I am writing unreservedly—because, with you, I wish always to tell the whole truth.—The other sister—C.—is more amiable, has more little talents, and is much more useful than M. but is yet a mere every day character. They are all three much very much behind your wife and mine. We, my dear Nicholas, have drawn the highest prices prizes in the lottery of marriage.

I have attended to your commissions—procured a new glass for your clock—had the lock and pistol repaired—placed the memo-apparatus in proper hands—& purchased a weighing apparatus: the book, too, which you have written for I will endeavour to trace and procure. The weighing apparatus cost me much trouble—I went to five persons, all of whom have patents, and all of whom which would have satisfied you—the difficulty was to choose; I was therefore determined by the price—and shall send you a dearborn’s balance with spanish weights. I think of adding to it a small English apparatus, which seems convenient. I have applied to Mr Heard for your a/c—; and will get from him the direction about the disposal of your chairs &c left in New York—and comply with it. When I have time to read over your letters I will see if there is any request of yours left unattended to—Before I sail I shall write you fully, and repeatedly: Cary & Co will be the medium of correspondence between us when I am in china—: they are most attentive and admirable fellows, and friends of mine. If you want agents in New York choose them.

dear N. I wrote the above seven days ago. We have a letter from Aunt Hackly, declining to take Ellen. she fears the responsibility—. We are going immediately to N Yk, to see her about this.—what say you to the washington duel. my view of it is precisely that of the New York American. yet I admired Leggetts admirable letter to Webb. I would send you the newspapers, but suppose that as Consul you get more than you can read. You recommend to me the Democratic Review; I subscribe for it—though its doctrines in this regions are like assafœtida, loathsome to the community of gentlemen.—at this moment Dr Reynolds, celebrated for his skill in diseases of the ears and eyes is coming to examine Randolph. I have but little hope that he will ever recover in any degree his hearing. Flagg, the dentist, told me the other day that if there had been a discharge from the ears the tympanum becomes indurated and the disease incurable. kindest love to dear Virginia—. If I go from New York to Phila (possible) I will go and see your boy. Say what is necessary for me to Septimia. and believe me ever yours faithfully and affectionately.

The washington duel between United States Congressmen Jonathan Cilley of Maine and William Jordan Graves of Kentucky on 28 Feb. 1838 resulted in Cilley’s death. Newspaper editor James Webb, responding to a rumor that Cilley had abused him during a heated congressional debate, sent a written challenge to Cilley through Graves. When Cilley refused to accept the note, Graves took that as an insult to his own honor and challenged Cilley on the spot.