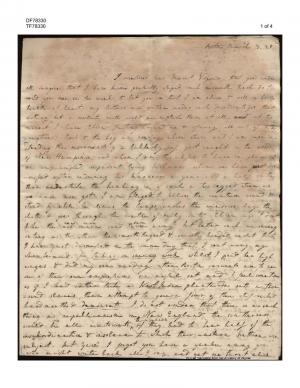

Ellen W. Randolph Coolidge to Virginia J. Randolph Trist

| Boston March 13. 29 |

I sometimes fear, dearest Virginia, that you will all imagine, that I have become perfectly stupid, such miserable trash do I send you once in two weeks, to let you see that I am alive, & well in bodily health at least, my letters are written under such disadvantages that nothing but a resolute will could accomplish them at all. and at this moment I have Ellen flitting around me & offering all sorts of interruptions, Bess & the boy are roaring above stairs, and I am superintending the movements of a lubberly oaf just caught in the woods of New Hampshire, and whom I am thankful to have in place of an unprincipled impudent lying Irishman, whom we have just dismissed after enduring his knaveries a year and a half rather than undertake the breaking in of such a two legged steer as we have now got. I am obliged to follow the creature round & stand by while he cleans the lamps, washes the windows lays the cloth & goes through the routine of daily duty. Ellen says “I dont like the noo marn send Sarm away”1 but better such an ourang outang as this than the smooth tongued & smooth handed varlet that I have just dismissed on the same day that I sent away my chambermaid for taking in sewing work, whilst I paid her high wages & did my own mending. these Boston servants are, to use one of their own expressions, an awful set, and I feel sometimes as if I had rather take a West India plantation with a thousand slaves, than attempt to govern four of these stiff-necked hard mouthed democrats. I do not wonder that there is no such thing as republicanism in New England, the southerners would be all aristocrats themselves if they had to bear half of the insubordination & insolence to which their eastern brethren are subject. but “gare” I forgot you have a yankee among you who might write back all I say and get me burnt alive. so burn my letter instead. I hope your boy has improved in manners since you last wrote. mine, who is still without a name (owing to Joseph’s abhorrence of his own, and my disinclination for any other, founded on what I believe to be the proprieties of the case) my boy although not at all cross is very troublesome. he keeps me awake all night by his extreme restlessness, & without once crying contrives to disturb me as much as yours can do you. oh it is a wearisome thing [. . .] to be a woman, after all, and if it were not for our hopes and our affections there are few of us who could bear all that is laid upon our shoulders; but in the midst of our troubles we are always comforted by the thought that we are serving those we love, or by the fond belief that some time or other we are to see better days.—Tell Mama that Mrs Swett after passing her time a full month has at last had the witch knots untyed and is “lighter” of her son; a fine boy weighing nearly ten pounds who came into the world without causing any trouble to his mother, and is, along with her, doing remarkably well. the family are greatly delighted & in the joy of this happy event seem to forget entirely that they have another lad bairn among them. my poor little boy is sadly thrown into the shade, and if he were to be snatched from me his father’s heart and mine are I fear the only ones that would feel it. this is one of the sorrows arising from a separation from my own family, that my children have no one to care about them and I feel as if they were to grow up without friends. my good kind old grandmother who has always been so kind to me will not last much longer, and my excellent Aunt Storer is so removed from me by a residence out of town that I seldom or never have my heart lightened by her presence.—Mrs Thomas Coolidge has been ill a long time and is just able to leave her chamber—she is a very amiable and interesting woman but I fear will never have any health. What a jeremiah kind of letter I have written to you dearest Virginia! I am ashamed of it, but it is now to send this or none and this will at least tell you that I am well and my babies also. as you may suppose I go out not at all but I have some pleasant neighbours who come in now and then & chat half an hour with me. I have lately made acquaintance with one of the most spirited and talented women I ever knew. a Miss Moss, one of four old maiden sisters, many years ago emigrants from Halifax, Englishwomen by birth—they kept a school for their support a long time, but are now rendered independent by the death of an old uncle; the two youngest are very ordinary women, the eldest an excellent house-keeper, the second full of talent, animated, eloquent, witty & highly educated. rather satirical & a thorough-paced englishwoman who has never become at all americanised. she amuses me exceedingly. her powers of conversation are equal to any I ever knew, & remind me [. . .] of the dialogue of Sheridan’s plays than of any thing else. she [. . .] as witty and as caustic as lady Teazle, but withal not ill-natured. farewell my dearest, Ellen is a whole legion of little imps in one this morning, and has been tease, tease, worse than a nose-fly, & Sarm has been floundering about “like a greasy headed dray horse” ever since I began to write. I asked Nell if she did not want to go and see you all & her ready answer was “tell ganma I should like to go but my dear great Katy is too sick.” great Katy continues her idol and being an object of passionate admiration to Bess also, there are frequent battles for her possession. she has neither head nor arms and is like what I suppose the princess in the Persian Tales must have been, she whose mouth was in her huge breast, and who deemed a head nothing more than a hideous excrescence. dear love to all, Jane, Jefferson, & their bantlings. Tell Mama her friends always inquire after her health and well-being, & Cornelia’s the same, I always forget to tell C— the speech made to me by Mr Dorr an “amiable rouè” whom she recollects. “Mrs Coolidge have you heard from your sister lately. I wish she were five years older than you, and could fancy an old bachelor like myself.”