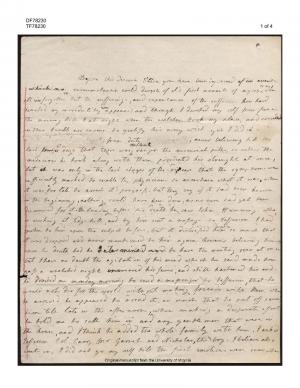

Martha Jefferson Randolph to Ellen W. Randolph Coolidge

| [30 June 1828] |

Before this dearest Ellen you have been informed circumstances of an event which no circumstances could divest of it’s first moments of agony to us, when all is was forgotten but the sufferings, and repentance of the sufferer. how hard hearted my incredulity now appears; and though I devoted my self from five in the morning till 9 at night when the watchers took my place, and considered neither trouble nor expense to gratify his every wish yet I did it with a [. . .] heart, from duty [. . .]; never believing till the last five four or 5 days that there was the least danger. the mercurial pills, or rather the medecines he took along with them, prostrated his strength at once, but the it was only in the last stages of the disease that the symptoms were sufficiently marked to enable the physicians to ascertain what it was, when it was too late to arrest it’s progress. but they say if it had been known in the beginning, nothing could have been done, as no cure had yet been discovered for it. the Sunday before his death he saw John Hemmings who is working at Edgehill, and by him sent a message to Jefferson. I had spoken to him upon the subject before, but it distressed him so much that it was dropped and never mentioned to him again. however believing himself upon his death bed he made up his mind determined to have the meeting over at once but I have no doubt the agitation of his mind which he said made him pass a wretched night [. . .] increased his fever, and still hastened his end. he desired me monday morning to send a messenger to Jefferson, that he would not die for the world with out making friends with him. whe[n] he arrived he appeared to dread it so much that he put off seein[g] him till late in the afternoon, when making a desperate effort he told me to call him in and any gentlemen that were in the house, and I think he added the whole family with him. I asked Jefferson Col. Carr, Mr Garret and Nicholas, the boys, I believe also went in, I did not go my self till the first emotions were over, when I went in did he seemed to be addressing them all, he said he was a unita[ri]an christian, that his faith since he was 17 years old had been the sam[e] with My fathers. he then addressed him self more particularly to Jefferson. he said they had said many hard [. . .] things of each other, he offered and begged of him mutual forgiveness. he said it was folly to for a dying man to talk of forgetting, but that he would live many years and begged that every thing might be forgotten. he said in presence of us all “an honester man exists not.”1 he exculpated him entirely, and again asked his forgiveness. he said some thing kind and affectionate to each in his of the Gentlemen, spoke of me as his adored wife, and his children with great affection generally, but naming none particularly, absent or present in the course of his disease he had repeatedly spoken of you and your children and seemed much pleased when I told him how much Ellen reminded me of your childhood by her signs and vivacity. his blessing, as he said himself all that he had to leave, he left to us all. and seemed anxious to atone for the errors, blunders he called them of his past life. he said he wished to atone for them by his death sufferings death bed sufferings. he told Jane that his heart was not bad, but that he had been hurried away by the violence of his passions. that had he have followed the dictates of his head his conduct would have been very different. he seemed to have it much at heart to prove the soundness of his that at all times. he died at peace with every body. but in the course of his long illness, the same suspicion, impatience, and propensity to argue upon the most trifling circumstances even the injudicious arrangement of a pillow, shewed it self as strong as in health. no single nurse could have stood the fatigues of his sick bed. but Jane staid with us the last four days and her self the girls and My self nursed him during the day. our kind neighbours, Jefferson & the boys during the night. he seemed anxious for Jefferson to be with him, enquired repeatedly for him if he went out, and begged him to be with him when he died. the last night & morning he suffered dreadfully with sick stomah stomach and pain in the bowels, but for four or five hours before his death he slept quietly and expired in his sleep with out a struggle or a groan. I have dwelt upon this painful subject My dear Ellen, because I thought that the details were such as to be a comfort to you. his last wishes were executed in every point but one, having the funeral service performed over him by Mr Hatch or Bowman against whom & Mr Bowman at an early stage of his disorder he had objected. but we thought that in his last moments his mind had softened so much that he would have recalled that, as he had done the strange [. . .] directions for his shrouding and bury burial and that it would confirm the idea of his insanity. to have not [. . .] he said if Mr Meade ever came in to the neighbourhood [. . .] any future day and would bury him for[. . .] he might do it. but not other wise —Mr Hatch read the service, & when Mr Meade comes, we mean to get him to preach the funeral sermon. in every thing else his slightest wish has been obeyed. I shall never cease to rejoice that I sacrificed my wishes which I acknowledge were to have remained till2