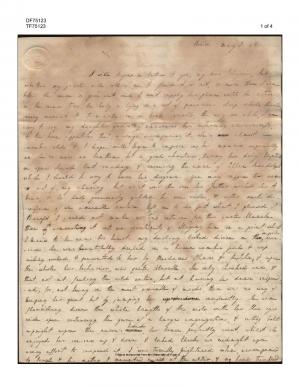

Ellen W. Randolph Coolidge to Virginia J. Randolph Trist

| Boston May 9. 26. |

I will begin a letter to you, my dear Virginia, but whether my jewel will allow me to finish it or not, is more than I can tell. the nurse is gone out and I must supply her place until she returns. in the mean time the baby is lying in a sort of precarious sleep which threatens every moment to terminate in a loud squall, the way in which, I am sorry to say, my daughter generally announces her returning consciousness, & the keen appetite that always accompanies it. she is now almost six-weeks old & I hope will begin to improve in her manners especially as she is now no heathen, but a good christian, having been duly baptisd in open church last sunday & receiving the name of Ellen Randolph which I should be sorry to have her disgrace. you may suppose this name [. . .] is not of my chusing, but as it was the one her father wished her to bear, & he had generously yielded his own wishes, & after much discussion of an amicable nature, left me to do just what I pleased, I thought I could not make a less return for this carte blanche than by to converting it into an opportunity of obliging him in a point which I knew to be near his heart. my darling looked divine on tha the important occasion. she was beautifully dressed in a linen cambric frock & cap richly worked & presented to her by Mesdames Shaw & Ritchie, & upon the whole her behavior was quite tolerable; she only shrieked once; & that, not at feeling the cold water, but at having her dance suspended, for, not being in the most amiable of moods, there was no way of keeping her quiet but by jumping her up & down incessantly. she came flourishing down the whole length of the aisle with her blue eyes wide open returning the gaze of a large congregation, & sitting bolt upright upon the nurse’s arm hand, her head perfectly erect, whilst she enjoyed her see-saw up & down & looked black as midnight upon every effort to suspend it. I was terribly frightened when, accompanied by Joseph & his mother, I presented myself at the altar, & my hands trembled in such a manner when Mr Greenwood deposited the baby in them that I could scarcely receive her; I have not had such an alarm since the day I was married, although there were two other mothers presenting their children at the same font, to keep me in countenance. the three little damsels received the benediction to one after the an other, waited with great gravity until the ceremony was entirely over, & departed with the utmost decorum, each her own way home. I detained the monthly nurse until this business was over, as I had neither strength to hold the baby for such a length of time nor skill to keep her quiet. I am expecting every hour now to be left with her to my own management, & that of a nurse in whose competency I have not much confidence. oh! what would I give for Sally now.—We have at last beautiful weather, after a great deal of very unpleasant. poor Cornelia has had a dismal time so far; in a strange place & confined almost entirely to the house by bad weather & my inability to go abroad with her. I knew it was selfish in me to wish her to come at such a time, but she is such a comfort to me that I am not disinterested enough not to rejoice in her presence.

May 10. my sovereign lady waked just when I had reached this point dearest Virginia, & I intended to have asked C. to finish my letter that it might reach you on monday, but at the same moment came in a young lady between whom & Cornelia a most romantic friendship has sprung up as quickly as one of Mother Glass’s salads. your letter of May 3d arrived this morning & to your question whether the birth of a baby is as bad as having all your teeth drawn at a sitting I can only remind you of what Napoleon said to O’Meara, that the worst of all pains is the one under which we happen to be suffering. of one thing I feel confident that you will never be as much alarmed at the birth thought of an-other child as you are at present, for the very mystery which overhangs the subject before we become acquainted with it enhances to a dreadful degree our appret apprehensions as to the event. we imagine it something very extraordinary & out of the common way, & find it to be one of the simplest natural operations. it is like a riddle, which when once found out, you wonder how you could ever have wondered about it. I do not attempt to deceive you as to the pain, but upon the whole you get through with it infinitely better than you could possibly conceive without having experienced the strength & support that is granted to a woman even in the hardest part of the operation. of one thing I am quite sure; if you could be seated at the foot of my baby’s bed (supposing her yours) as I am, & hear her breathings, & see the top of crown her little black head peeping from under the clothes, you would agree to go through twice as much rather than be without her. As to having a doctor in the house, why cannot you send for Dr Gilmer. he is very skilful in this branch of his profession. not that I do not think Aunt Scilla entirely competent to all ordinary cases in which Nature does her ow[n] work & will admit of no interference, but that it might [. . .] happen with you, as it did with me, that blood-letting would quicken the business & spare you some sharp pains. however in my case this proceeded I presume from my being so ancient & tough—you are the very form & the very age, according to the Yankee notions, to do exactly right. my form was in my favor, but my age had exceeded about four or five years the right point, between youth & too full maturity. & as to the size of the baby, I wonder where two such thread papers as Nicholas & yourself could pick up flesh enough to make it weigh 14 oz. much less 14 lb. mine was thought prodigious for it’s opportunities at 8 pounds. I am sure yours cannot be more—what an abominable letter; ! throw it in the fire & drive away all your blue devils, & do not wish for more [. . .] frighten yourself at having to suffer what so many women are willing to incur for the sake of a second husband when they cannot plead the excuse of ignorance. a great deal of love to all dearest Virginia and pardon this stupid scrawl. I have been interrupted twenty times & know not what I have written. I wrote to my dear mother last week, & shall to Mary the next farewell my love I am in a desperate hurry & my baby, that chorus to every verse of my song when not the only theme, has got up & is fretting for her lunch.