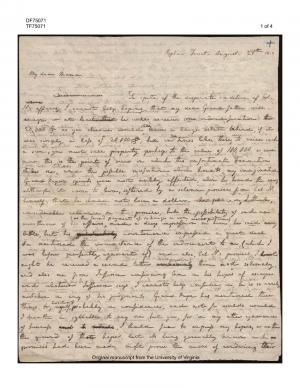

Ellen W. Randolph (Coolidge) to Martha Jefferson Randolph

| My dear Mama | Poplar Forest August 24th 1819 |

In spite of the desperate condition of Col. N’s affairs, I cannot help hoping that my dear Grand-father will escape, or at least that he will receive some indemnification. the 20,000 $ as you observe would still leave a large estate behind, if it was simply a loss of 20,000$, but in times like these, to raise such a sum, you must sell property perhaps to the value of 100,000 or even more. this, is the point of view in which this unfortunate transaction strikes me, and the possible misfortune which haunts my imagination. Grand Papa’s spirits were most visibly affected, when he heard the news, although it came to him, softened by a solemn promise from Col. N. himself, that he should not lose a dollar. he placed, I think,considerable reliance on this promise, but the possibility of such an overthrow of his affairs (as the forced payment of so large a sum would produce) made a deep impression on him; he said very little, but his [. . .] countenance expressed a great deal. He mentioned the circumstance of the endorsement to me, (which I was before perfectly ignorant of) and also, Col. N.s. promises. I [. . .] last night he received a second letter [. . .] renewing them most solemnly, and also one from Jefferson confirming him in his hopes of escape. and whatever Jefferson says I cannot help confiding in, he is so rarely mistaken in any of his judgements. Grand Papa has mentioned these things to me, Cornelia & myself, probably in confidence, and not for worlds would I breathe a syllable to any one but you, for in my utter ignorance of business and its details, I should fear to express my hopes, or rather the grounds ground of that those hopes, lest its being generally known such a promises had been made, might prove the means of rendering its their fulfilment more uncertain—silence is at least the safest plan, for no [. . .] harm can be done by that. besides that I should not think myself justifiable in repeating any information Grand papa might give me on the subject of his affairs, out of the immediate circle of my family.

I have always considered Col. N. as a man of the highest honor, and yet I can scarcely reconcile his present situation with my ideas of honor—it is impossible he should have been unacquainted ignorant of the precipice on which he stood, and yet to suppose that he would has involved such numbers in his ruin, merely to put off the evil day; and to delay for a short time a fate he should must have known inevitable; this conduct is worse then dishonorable, and I will not, cannot believe him capable it of it—it would shake my general confidence in mankind; I should never again know whom to trust if a life of unsullied rectitude is no guarantee against the commission of such acts. but at present all my thoughts center in my dear Grandfather; let his old age be secured from the storms which threaten us all, and I would willingly agree to abide their peltings. I am almost ready to fix my ideas of right and wrong on this single point; to believe every thing honorable which can save him—every thing base, vile & dishonorable, that tends to obscure the evening of such a life.

You say nothing of poor Jane, nor how she bears these accummulated distresses; nor whether she is acquainted with the Siroc influence which her father has exercised; and the desolation which marks his path. but of this no more, I had rather think and talk of almost any thing else.

Cornelia and myself have had our visit to Bedford rendered less comfortable than usual, by a variety of circumstances, and we look forward with more than usual satisfaction to the period of our return—Grandpapa proposes to leave Poplar Forest the evening of the 12th and we shall dine at Monticello Tuesday the 14th. I look forward to my long fall visit with some anxiety; I do not know whether my desire of improvement will prove sufficiently strong to bear me through this long melancholy1 retirement. however the affection for my dear Grandfather which makes a voluntary exile of me, will perhaps render me a cheerfull one. In spite of all interruptions, I have done about four times as much as I have ever done been able to do in the same space of time, at Monticello. I am reading the 5th volume of Toulongeon, and have some hopes of finishing it before I return. I read sometimes as much as a hundred lines in of Virgil in the day, besides a good grammar lesson and latin exercise, and by only devoting sunday morning to the spanish verbs, I have made good progress in them. if I only had a piano, that I might not, whilst improving in other things, be falling off there.

We have received great kindness and attention from our neighbours, particularly Mrs Walker, who is constantly sending us little presents. [. . .] about once a week we see [. . .] arrive a tidy mulattoe girl, with an apron as white a snow, & a nice little basket with a napkin thrown over it, in her hand. sometimes, fruit of different kinds, melons apples, ripe peaches &c, then again vegetables, and on one occasion cake and sweat sweet meats. you will laugh to hear that lamb has become such a rarity, that we were greatly pleased to receive from the same kind old lady, a quarter of one, very fat and tender. we have lived altogether on chickens, being unable to keep fresh meat for want of ice. we get snow enough from Mr Radford’s, (for which we send every other day) to give us hard butter and cool wine—Whilst Israel Cornelia and myself were chief butlers; Grand papa insisted on our using that filthy cooler, (refrigerator, I believe he calls it,) which wasted our small stock of ice, and gave us butter that run about the plate so that we could scarcely catch it, and wine above blood-heat—but on Burwell’s recovery, he soon scouted it, (to use Aunt M’s favorite expression) and we have been quite comfortable ever since. We are not as you may suppose, able to keep up the trafic of presents with Mrs W. but some bottles of red wine, a few crackers, and a part of our nice south-Carolina rice, have served to shew her that our wills were good; and when I began to speak of the old Lady, it was principally that I might ask you to send by Henry something for a for us to give the maid who trudges through all weathers to bring her mistress’s presents. money I suppose is too scarce an article to render that practicable, but any thing which you think will do; we have nothing with us but necessary clothes, and I have felt quite ashamed to dismiss her so often unrewarded for her trouble—there are in fact two of them, but one comes oftener than the other.

Grand-papa wants to breakfast at Warren on the morning of the day we reach home. will the family be there?

Did Mary neglect to ask Browse for the crayon, has he none to give or did he forget the request. however it is now too late, and was never of any importance, being merely the gratification of a whim.

I have written quite regularly to Aunt R. and indeed I have devoted more than half of one precious day in every week to writing to my friends.

Give a great many kisses to Geordie, I am so much afraid the cool weather has made his mammy pull his frock up on the shoulders, so that I shall not see them naked, the first thing, when I arrive.

Adieu my dearest mother, give a great of love to Papa and the girls, (including Aunt M. & Mrs Trist ) Aunt R. is not with you) and believe in the constant affection of your daughter.

Grand-Papa has almost entirely recovered from his rheumatism.